I wasn’t in Wisconsin, for I was never this weary in Wisconsin.

And the ground was too white, the sky untroubled by jet contrails. The big cat stalking through the trees before me, golden eyes burning in fearful symmetry, told me how far from home I really was.

I was in Siberia.*

The tiger studied me for a few long heartbeats, then turned and padded slowly away. I didn’t blink, never took my eyes off her. You must understand that I watched her purposefully, believing that my life depended on it. Then you can understand my awe when she vanished into the trees like a ghost. Her colors, her pace, her practiced path were as much a part of this place as the soil and the rock. I noticed then that my feet were cold. I was deeply envious of the tiger.

I scratched at an itch behind my ear. My fingers came back bloody. Injured, cold, lost, alone. Could have been worse. Could have been raining.

Thankfully, at this thought, it did not start raining. I pulled my phone from my coat pocket. Its screen had cracked. It had no signal. And it alerted me that I was, “dangerously low on space.” I wiped my fingers clean on my pant leg and flipped through my photos.

There were Jodi, Ella and Collin, my dog Taz, pictures of my parents with the kids. The time on the phone said, 35:35. So, there were still limits to these things. The sun was up, and I was hungry like it was the afternoon. But I wasn’t sure. I kept flipping through, again and again.

Time was different here: slow, silent and cold. Back in Wisconsin, things were bustling and noisy. We live within time, bound by it, paced by it. School buses and station breaks on the radio. Time is working through lunch, it’s brewing coffee, it’s beating traffic.

Here, it was only daylight. It could have been any day in the last twenty million years on Earth under a sunny sky.

A year ago I read a book by the physicist Carlo Rovelli called The Order of Time. In the first part of the book, he disillusions the reader of some of the practical ways that people think about time. For instance, the “present” — as in, this very moment in time — doesn’t exist. If something changes, if something moves, the event can’t be experienced without light taking time to reach another party. The light from the tiger reached me all too quickly, for we were very close. But the light of my life in Wisconsin wouldn’t reach me for many years, if it ever does again.

In addition to the present not being real, another of our illusions is that the past is separate from the future.

As I looked from image to image in my phone, at the tender delight in the eyes of my kids, as I remembered the rush of purpose around my wife, beautiful and real, I knew that these memories of the past were also shapes of the future.

From Siberia, the past and future of Wisconsin were equally remote. All the roots and fruits of my life there, and all the possibilities of the years and generations to come were far more than a world away. The way home was interstellar. I looked at those photographs until the screen dimmed and went black.

Night had come. Thousands of stars came with it. It was time to sleep in the taiga. I found a great old spruce, boughs wearing a heavy coat of snow, and I curled up beneath it. The fallen needles there made a soft brown bed. The close air was sweet with animal musk. A deer or an elk had spent at least a night here. I shivered to sleep and dreamed of my sweethearts, of my wife.

And over the following days and weeks I joined the humus and sated the hunger of forest prowlers and crawlers. I was past and future as calories and memories. A part of life, a sliver of time, in Wisconsin and Siberia.

* Truthfully, I was sitting quietly in our minivan waiting for my son to get out of school. I had hit my head earlier on an open cabinet door. It had already stopped hurting. There was no tiger. After school, my son had a peanut butter and jam sandwich. I had a cup of coffee.

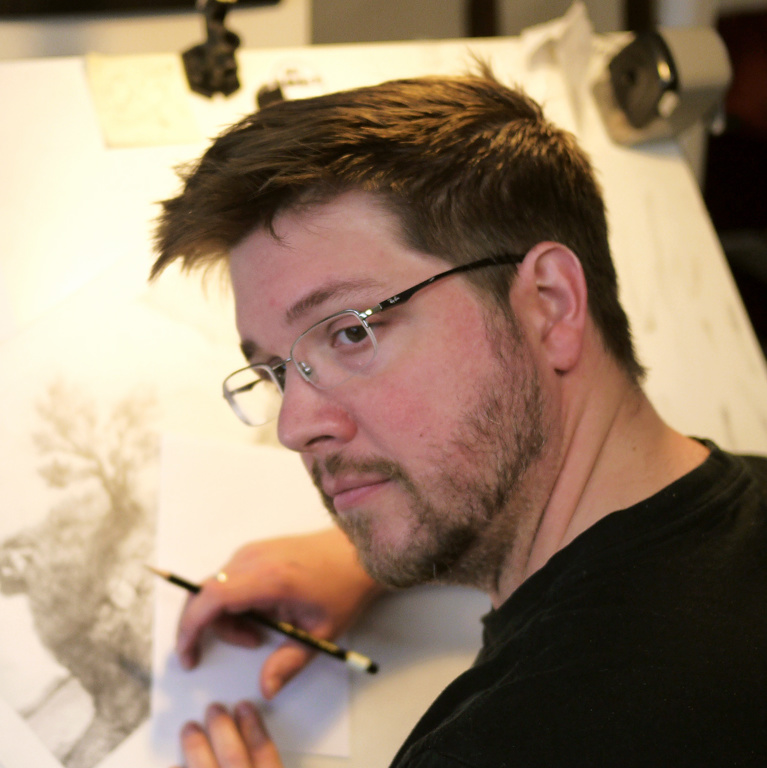

– Micah Clarke

Micah Clarke is a father of two, a husband of one, a son of two, and a brother of one. He draws a lot, paints very little, and writes children’s books. Is a book a book if no one has ever published it? If not, he’s still a draftsman and a very little painter. He likes his eggs over easy, with grits and crispy bacon. And he wants you to know that he’s grateful to you for taking time to read his posts.